D

o you want your learners to collaborate? To demonstrate leadership skills? To drive towards a goal? To evaluate and analyze situations before committing to a decision? To value the perspectives of others? To improve performance?

o you want your learners to collaborate? To demonstrate leadership skills? To drive towards a goal? To evaluate and analyze situations before committing to a decision? To value the perspectives of others? To improve performance?Then you definitely want them playing games.

Most of us have probably played Monopoly. You know, the strategic decision-making, asset-leveraging, and negotiation skills tool?

What’s that you say? Monopoly is a kid’s game where the biggest decision you make is whether you want to be the thimble or the dog? And it’s just a game, because you roll dice, and the dice determine what happens?

Well, let’s think about that. Yes, Monopoly has an element of luck (so does real life!). But what drives a winning strategy in Monopoly?

- Strategic decisions on what assets to purchase

- How to leverage those assets by improving them and driving larger ROI

- Building alliances that enhance your ability to compete

- Negotiating with others until you’ve maximized your revenue stream

Does your audience need any of those skills?

But let’s not stick with old school board games. Today’s Role-Play Games (RPGs) and Alternate Reality Games (ARGs) are not the single-user joystick games of years past. They require collaboration, team building, smart use of resources, strategy, and follow-through. And the most successful RPG players also tend to be great leaders and team-builders.

So am I recommending that we commit large swaths of business time to playing Monopoly and World of Warcraft? Not really (although that would be fun!), but I am recommending that we identify and utilize the elements that make these games so effective:

- Competition: Every business is a competition. Many internal function are a competition, too; competition for attention, scarce resources, funding, etc. Games are inherently competitive. Learning how to be a better competitor will also make you a better businessperson.

- Engagement: I can’t learn anything if I’m not paying attention. Why teach me an abstract skill when you can get me to engage in the actual behavior? Games get me involved, give me a goal, and help me understand what I have to do to hit that goal. All fairly painlessly—in fact, I might not even realize that I’m supposed to be learning.

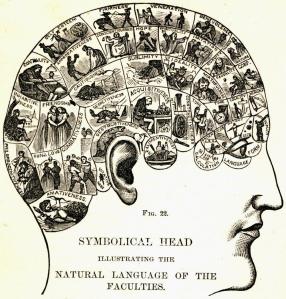

- Social learning: Whether we’re playing our game in a real-life room or playing online in a virtual space, we’re still working in a social environment. That means that we can create our own experience (within the rules of the game, of course), and the experience changes based on the people present. We can share our knowledge, experiences, assumptions, and learn from (and teach) each other. We may be playing a game, but what we’re learning from each other is very real. And that leads us to…

- Informal Learning: Game environments create wonderful opportunities for informal learning. As a team of people driving towards a goal, we inevitably share all kinds of knowledge. All the notebooks in the world won’t drive knowledge like an experienced colleague sharing a great story.

- Collaboration (or lack thereof): Great games use goal-based scenarios (more on that in the next post), where teams of people need to collaborate to achieve success. This is a great opportunity for participants to understand what each role brings to the table, how collaboration drives a better outcome. Learning this kind of behavior in a game is “sticky;” it will stay with you long after the game is over.

Reni: I read an article on The Economist titled:

Reni: I read an article on The Economist titled:  Rich: I attended several learning conferences this year, and at each one, I heard some variation on this message: it's time to get past old school training models, because the generation of 20-somethings entering the work force don't learn that way. We need social media for the 20-somethings, because that's how they learn. We need virtual environments for the 20-somethings, because that's how they learn. And every time, I wanted to scream from the back of the room, "HEY! I'M A 40-SOMETHING, AND I LEARN THAT WAY, TOO!"

Rich: I attended several learning conferences this year, and at each one, I heard some variation on this message: it's time to get past old school training models, because the generation of 20-somethings entering the work force don't learn that way. We need social media for the 20-somethings, because that's how they learn. We need virtual environments for the 20-somethings, because that's how they learn. And every time, I wanted to scream from the back of the room, "HEY! I'M A 40-SOMETHING, AND I LEARN THAT WAY, TOO!" Is there such a thing as too much reality?

Is there such a thing as too much reality?

quently build interest by inserting compelling story twists. I won’t include any spoilers, but most people will admit to being thrown for a loop when they learned the truth about Bruce Willis’ character in

quently build interest by inserting compelling story twists. I won’t include any spoilers, but most people will admit to being thrown for a loop when they learned the truth about Bruce Willis’ character in  story takes a twist when it unexpectedly starts raining frogs. And perhaps that’s the key difference between movie storytelling and learning storytelling. If your story completely deviates from reality, you’ll probably lose your audience. So your story probably shouldn’t have any froggy precipitation.

story takes a twist when it unexpectedly starts raining frogs. And perhaps that’s the key difference between movie storytelling and learning storytelling. If your story completely deviates from reality, you’ll probably lose your audience. So your story probably shouldn’t have any froggy precipitation.