Part 1: Teaching New Hires How to DO Their Jobs

The goal of any new hire program is to get new team members trained and up and running in their jobs as fast and as effectively as possible.

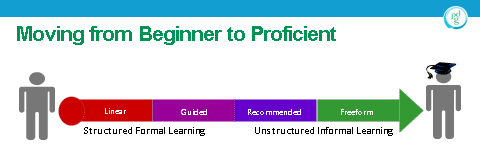

When people are learning something new, they need structured formal learning because they “don’t know what they don’t know”. However, as they move down the continuum toward becoming proficient, they may still need to be able to reference training content to answer questions as they “get stuck” but this environment has to be unstructured and informal letting the learner drive their learning experience.

I suggest ALWAYS designing and developing learning interventions with a performance and business goal in mind. Structured formal training programs are a great way of getting learners started with learning something brand new, but providing reinforcement of that learning after the fact, back on the job, is a critical component of ensuring people achieve performance goals as quickly and as efficiently as possible.

Remember that Hermann Ebbinghaus’ Forgetting Curve tells us that from the time your learners leave the training program, let’s say at 5 pm one day, to 9 am when they come back the next morning; they will have forgotten approximately 35% of what they learned. Amazing isn’t it? I remember the moment I learned this fact and I wondered what I was doing in the learning profession. Then I learned that with reinforcement we can raise the forgetting curve and dramatically increase memory.

Imagine the following scenario: A learner goes through the new hire training program, and is introduced to all the new concepts and processes that she needs to know, but that doesn’t mean she can now perform proficiently. She will still struggle as she tries to remember all the information, such as the details associated with process steps. In fact, cognitive research about the brain and its capacity to remember has proven that people don’t initially remember all the details of what they learn—what they initially remember is the high-level concepts, the big picture, the key points. Consequently, what they initially forget is all the details of how to execute various processes.

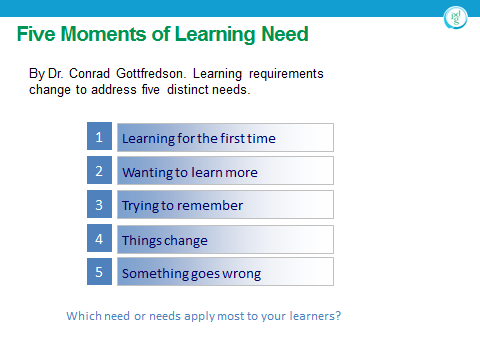

In fact, research shows that there are five distinct moments of learning need.

Consider this example:

Consider this example:

- If the learner is learning about a new process, there will be a time initially where they are learning for the first time

- Perhaps as they become more knowledgeable they will want to learn more about the process, how their process fits into the processes around them, and what exactly happens downstream and upstream from them so they can be mindful of how they execute their part of the process

- There will also be times when the learner may forget some of the process steps

- Especially for infrequently used processes, there will surely be times when the learner is stuck and is trying to remember

- Finally, something goes wrong and the learner has to figure out what it was and how to correct it.

In the first part of this series, we talked about the role of the individual in learning. It’s hard to make someone learn if they’re not willing. But what if they are willing but are not encouraged or worse are discouraged by the person who judges their performance: their manager? What is the manager’ attitude toward the new knowledge and skills learned?

In the first part of this series, we talked about the role of the individual in learning. It’s hard to make someone learn if they’re not willing. But what if they are willing but are not encouraged or worse are discouraged by the person who judges their performance: their manager? What is the manager’ attitude toward the new knowledge and skills learned? Challenge 1: How does this relate to me? Can you recall a time when you were totally uninterested and unmotivated to learn? Maybe in grade school during history class? For me it was college math. I simply was not interested. Why? I did not ever think calculus was something I would use in “real life.”We know from adult learning principles that people learn best when they can see the relevance the content has to their day-to-day jobs, and to their lives. So, one would think the answer is simple: show people how the content is relevant to them, and they will be open to learning it. As important as this concept is, it’s something designers forget to do as they get all caught up in designing the learning.

Challenge 1: How does this relate to me? Can you recall a time when you were totally uninterested and unmotivated to learn? Maybe in grade school during history class? For me it was college math. I simply was not interested. Why? I did not ever think calculus was something I would use in “real life.”We know from adult learning principles that people learn best when they can see the relevance the content has to their day-to-day jobs, and to their lives. So, one would think the answer is simple: show people how the content is relevant to them, and they will be open to learning it. As important as this concept is, it’s something designers forget to do as they get all caught up in designing the learning.