Is there such a thing as too much reality?

Is there such a thing as too much reality?In my first post on this topic, I said this:

“So how do you apply some of the rules of storytelling to our training initiatives? The key is to focus on how the world works in real life.”

The great thing about writing novels or screenplays is that you can make everything up. You’re not bound by the reality of what’s possible. But in a learning story, there needs to be some grounding in reality, however tenuous. In my simulation work, we often get hung up on reality. Does the simulation environment need to be a carbon copy of the real world? Arguably, the answer is no; one of the reasons we don’t always learn effectively is because our environments are full of distracters; your learning story can focus people on what’s important. But aren’t those distracters part of the learning experience? If you give me a nice clean environment to learn in, won’t I just have difficulty applying it in real life?

So how real do you need to get? The answer is, it depends. And not in a philosophical way. The real question is, what are the variables that need to be considered to tell the story effectively?

The most recognizable kind of simulation is probably the flight simulator. The failure to fly a plane properly will likely lead to mechanical failure, damage, and death. There are so many factors that can lead to failure (gauges, mechanics, alertness, weather, etc,) that flight simulators need to be completely realistic. The adherence to reality in a flight simulator is remarkable.

But in many environments, we want learners to focus on specific items. Where, in fact, presenting the whole reality of the job might actually be confusing. So it’s generally okay to leave stuff out or consolidate stuff. How do you that? Well, there are no hard-and-fast rules, but here are some guidelines:

1. Make sure you the stuff you leave out won’t distract the learner.

For example, if the learner works on a team where all of the members are in different cities, they might be distracted by a story that involves a scenario where everybody is co-located; however, they might be fine with a story where some team members are co-located and some are distributed.

I worked on a customer service simulation design with a company that made many different types of paper and packaging products. The client was very concerned that no one scenario (food packaging, office paper, print stock, etc.) would resonate with every member of the audience. Ultimately, we made the decision that the company in the simulation made bottles instead of paper. This way, the manufacturing and customer service environment was very recognizable to learners, but they weren’t distracted by the fact that the company didn’t make their exact paper product.

2. Make sure you leave in the stuff that makes the job challenging.

If we go all the way back to the beginning of this series, we established that one of the powers of storytelling in learning is that you can focus on those areas that make a job challenging. Is it a demanding boss? An industry that’s consolidating? Technology that changes rapidly? Clients who don’t know what they want? The power of storytelling is incorporating these elements in a way that affects people emotionally.

3. Focus on the element of time

For example, some businesses are seasonal; in retail, Fall is all about planning for the holiday season, Summer is all about planning for back-to school. If you leave this out, your story won’t have resonance. Also true is the impact of time; some decisions look different if you play them out over time; make sure your learners can see the short-term and long-term impact.

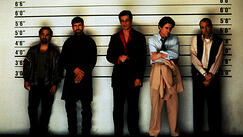

quently build interest by inserting compelling story twists. I won’t include any spoilers, but most people will admit to being thrown for a loop when they learned the truth about Bruce Willis’ character in

quently build interest by inserting compelling story twists. I won’t include any spoilers, but most people will admit to being thrown for a loop when they learned the truth about Bruce Willis’ character in  story takes a twist when it unexpectedly starts raining frogs. And perhaps that’s the key difference between movie storytelling and learning storytelling. If your story completely deviates from reality, you’ll probably lose your audience. So your story probably shouldn’t have any froggy precipitation.

story takes a twist when it unexpectedly starts raining frogs. And perhaps that’s the key difference between movie storytelling and learning storytelling. If your story completely deviates from reality, you’ll probably lose your audience. So your story probably shouldn’t have any froggy precipitation.